More clothing made more quickly: a forward march that culminates with the modern “fast fashion” industry. As the name suggests, today’s “fast fashion” industry places the utmost importance on speed of production and consumption. The consumer fashion industry now produces double the amount of clothing it did 20 years ago and is responsible for 10% of global carbon emissions. It’s a behemoth and an ever-growing problem for the health of humans and the planet.

In general, it’s a good thing that more of us can afford to buy the clothes we want to wear. After all, who doesn’t like feeling like you’re getting a good deal? But the price you pay at checkout is just one part of a garment’s true cost. In order to drive down the sticker price while still making a profit, fast fashion companies use a few strategies: reduce input costs by opting for harmful lower-quality materials, reduce labor costs through exploitative labor practices, and pollute the air and water extensively to avoid the expense of mitigation measures.

By Carter Baum. Carter was an intern at Bridging The Gap

Cost to Health

Beyond its heavy reliance on petrochemical manufacturing and supply lines that circle the world, fast fashion companies also use lower-quality materials and industrial applications of chemical coatings like formaldehyde that are toxic to human health. While the European Union has banned more than 30 of these chemicals from use in textiles, here in the U.S. we outlaw just 3—only from use in children’s clothing—meaning these carcinogenic substances are unwittingly invited into your home and all over your skin.1 Mild reactions generally cause a rash or itchiness while prolonged exposure is linked to heightened risk for autoimmune disease. As was the case with heavy metals used to process clothing in the 19th century, we have been slow to fully understand the health impacts of prolonged exposure to many of the petrochemicals used in clothing manufacturing.

Cost to Labor

In addition to using cheap but toxic materials, fast fashion further cuts cost through exploitation of the labor it employs. An investigation last year into Shein, the largest global fast fashion brand valued at $100 billion, found that Shein factory workers work 18 hours per day with just one day off per month and are compensated either a $556 salary per month or a commission of 4¢ per item of clothing.2 Four cents in exchange for the pants you nabbed at $10. The health impacts of working long hours are manifold: increased risk of cardiovascular disease, mental illness, and addiction. Most studies with these findings use 80 hours per week as an upper boundary. Fast fashion workers are exceeding 120 hours per week—a strategy that trades workers’ suffering for a further reduction in sticker price.3

Cost to Climate

And, of course, fast fashion’s impact extends beyond people to our planet’s climate as well. With clothing production skyrocketing ever upward, the demands of the industry for water and both natural and synthetic materials synthetic must too. Clothing consumption is up 60 percent worldwide since 2000 and even a simple t-shirt takes as much water to produce as what one person needs to drink over two and half years.4 It’d be one thing if all these new garments were finding homes where they would be worn for years. However, it’s increasingly consumers in wealthier nations who purchase these clothes despite having already well-stocked closets. 20 percent of clothes purchased in the U.S. are never worn at all. If they do get worn, fast fashion clothes are worn on average seven times before they’re discarded. In the U.S. alone, we will heap 21 billion tons of clothing on our landfills each year.5 And because of the heavy use of polyester and chemical coatings, much of this discarded clothing will sit in landfills and waterways for a very long time: currently estimates put it at 200 years.6

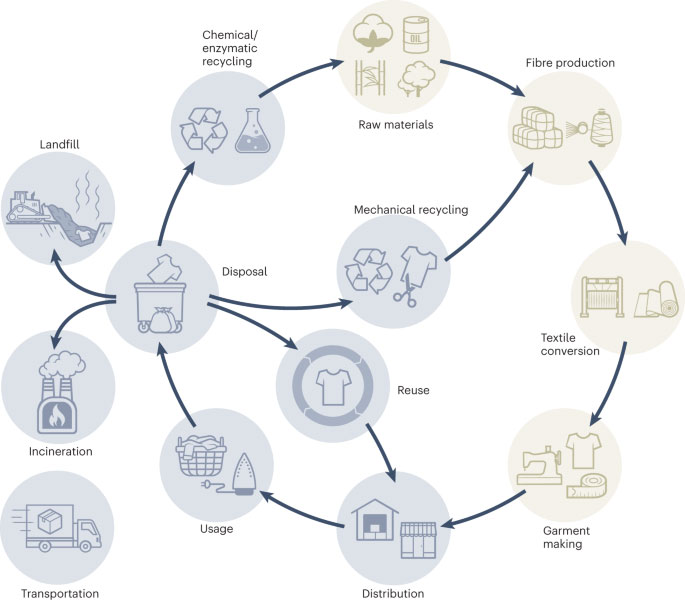

No matter how you look at it—if you’re willing to stop and do so—the price that you, workers, and the planet pay for those pants is a lot more than the $10 it cost you online. Fortunately, there are other good options, though, and even stylish ones. Rather than purchase new, cheaply made items of clothing, think about recycling old clothes or buying second-hand. If that’s not appealing, many smaller clothing brands make the effort to use sustainable materials, ethical labor practices, and responsible waste disposal that mitigate the hidden costs discussed in this article.

Without consistent labeling practices for clothing, shopping conscientiously can feel like a minefield. Still, there are numerous labels and certifications that help by highlighting brands with responsible business practices. Two of the best known certifications are given by Fairtrade, which is focused on ethical labor standards, and B Corp, which designates companies with holistic social and environmental responsibility goals. While we can’t change the industry overnight, we can make informed choices to change our own relationship with the clothes we wear to better align with our values.

There are many good resources to learn more about the problems associated with “fast fashion.” If you have a more visual learning style, this video by Teen Vogue does a good job laying out the facts.

Citations:

1 https://grist.org/health/clothed-in-chemicals-a-new-book-sheds-light-on-the-toxic-substances-we-wear-daily/

2 https://www.elle.com.au/fashion/why-is-shein-so-bad-27846

3 https://inews.co.uk/news/consumer/shein-fast-fashion-workers-paid-3p-18-hour-days-undercover-filming-

china-1909073

4 https://www.huffpost.com/entry/cottons-water-footprint-world-wildlife-fund_n_2506076

5 https://www.fastcompany.com/90311509/we-have-to-fix-fashion-if-we-want-to-survive-the-next-

century?utm_source=postup&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Fast%20Company%20Daily&position=1&part

ner=newsletter&campaign_date=03022019

6 https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1026&context=mgdr

7 Zhang, L., Leung, M.Y., Boriskina, S. et al. Advancing life cycle sustainability of textiles through technological

innovations. Nat Sustain 6, 243–253 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-01004-5