By Kristin Riott. Kristin is BTG’s Executive Director.

During the hottest days of summer in Kansas City, as well as other parts of Missouri and Kansas, we’re no stranger to moderate to severe droughts. Is there anything the average gardener can do to deliver water to parched plants, without standing around holding a hose for long minutes each morning, perspiring profusely, thinking about how high the water bill will look next month, and worrying about climate change?

There is. More than one thing, in fact.

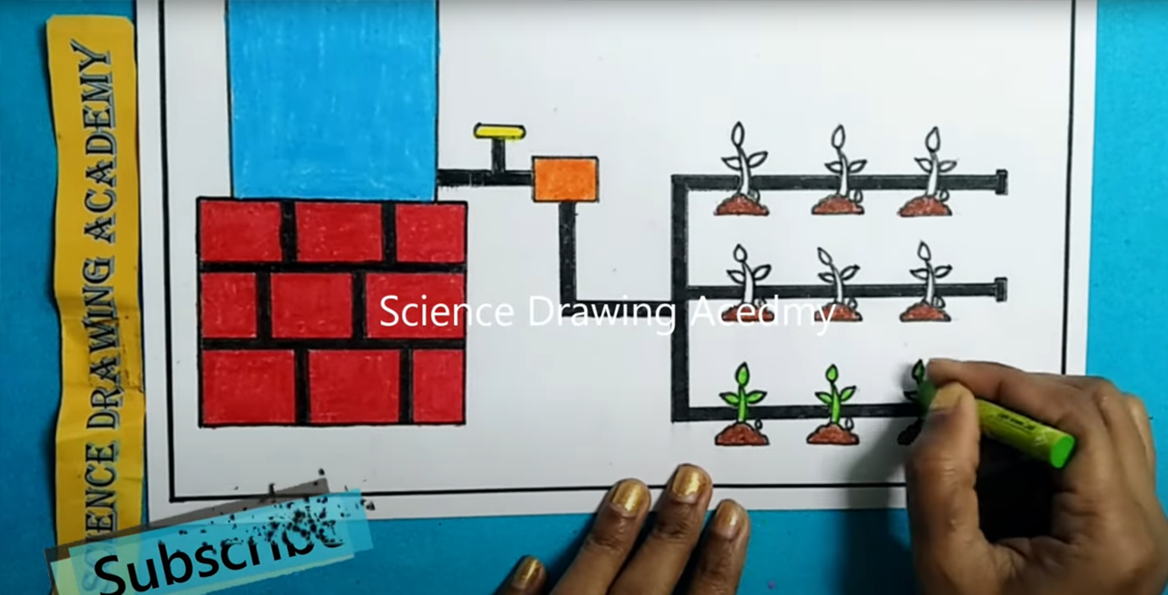

Let’s start with the solution that’s changing how farmers water plants around the world: drip irrigation. Rather than the usual practice of broadcasting a lot of water over the leaves of plants, most of which evaporates, drip irrigation delivers a thrifty amount of water directly to the plants’ roots. This solution is revolutionizing agriculture, and it works at the scale of a residential garden, too.

How? Residential drip irrigation systems typically attach a Y-shaped valve to the water spigot with the hose screwed in on one side and a timer on the other, so you can set the system to water as frequently or infrequently as you want. From there, the largest of a series of plastic pipes runs water out into your yard to where it can serve the most plants, then branches out with smaller and smaller pipes and water heads, which are designed to deliver more or less water for different plant sizes.

For my first drip system years ago, I sent a drawing of my garden, patio and water source to an online company, Dripworks.com; they called me, then drew a system and sent me a box with all the parts I needed and instructions to put it together. The hardest part of planning was figuring out where the main water hose was going to go, as sometimes it has to traverse the edge of a patio, for example, pinned into place so you don’t notice it. The installation of the system, then, took a morning. Once the system was installed, I started to save all kinds of time. All I had to do was “walk” the system every few days to make sure those blasted squirrels hadn’t chewed off anything, and the plants seemed to be getting the water they need.

Check out this video on drawing out your drip irrigation system.

If all this seems a little intimidating, start with a small set-up and add on from there. Maybe just run one plastic pipe out to your tomato plants, so you don’t have to worry about them, or the window boxes on the hottest side of your house. For a less complex system, you may be able to get most of what you need locally; just search for “drip irrigation supplies near me” and you’ll find plenty of options.

A couple of other notes: soaker hoses are not recommended so much the plastic pipes, because soaker hoses tend to get plugged up with mud and mulch, and they don’t deliver water as consistently or precisely. While rain barrels are much beloved and can help to save a modest amount of water (generally holding 55 gallons each), they can be very expensive and carbon-intensive, because the large barrel takes up a lot of shipping room. The KCMO recycling centers, which Bridging The Gap manages for the City, sometimes have rain barrels made from old food containers, which have a lower impact and cost.

There’s another way to avoid watering all the time: plant native plants, such as wild ginger for shade beds and baptisia or purple coneflower for sunny ones. We’ve blogged (link to previous blog) on this topic before. Natives DO need to be watered their first hot season or two, but after they’re established, their long root systems reach down and find moisture way below what most plants from Europe or Asia tend to. These Kansas and Missouri natives have had to evolve these root systems, to survive our harsh prairie climate, and they look fabulous, once you start climbing the learning curve. A couple of great sources for learning about and buying natives are Sow Wild Native, a local nursery on the east side of KCMO, Missouri Wildflower Nursery in Columbia, which delivers to the River Market and local plant sales during the growing season, and DeepRootsKC, a non-profit advocating for the use of native plants.

My only warning about natives is to make sure you know how they reproduce, to avoid highly invasive natives. I planted a kind of goldenrod which ran amok and took several years to eradicate; but I have another kind that is very polite and stays right in its place. Research every species you plant until you learn to avoid the “bad apples”, or else research “well behaved native plants” and start with those.

Native plants will reward you not only with less watering, once established, but they support a plethora of endangered moths, butterflies, and pollinators which bring life and beauty to your garden.