Land is constantly undergoing development throughout the Kansas City area. Apartments are built on formerly “vacant” lots, farmland is turned into suburbia, ranch-style homes turn into mansions, garages are added, driveways are repaved, irrigation is installed and patios double in size. Whatever the reason for construction, let’s observe what is on our land first to determine what can be preserved before it’s destroyed.

At minimum, undeveloped land in our area has valuable soil worth preserving as it took thousands of years to form. But this article is about trees. Kansas City has an incredible urban forest and we must try our best to preserve trees through development. As our steering committee member and MDC forester friend Chuck Conner says: “If your turf is damaged, I can replace your grass in one year. If you kill a 50-year-old tree, I can get you a new one in 50 years.”

If trees are damaged, they will need to be treated, removed or replaced. It’s often cost-effective to preserve the trees instead. Even if removal is necessary, it is better to do it before there is a brand-new driveway or roof in the drop zone.

How Construction Can Kill Trees:

- Root damage by excavation, trenching, changing soil grade or water movement and drainage

- Soil compaction by driving and parking vehicles and equipment in critical root zone; may be amplified if soil is moist or clay-like

- Injury by hitting trees with equipment or placing soil and debris against trunk and root flare

- Chemical damage from dumping fuels, oils, paint thinners, etc.

- Removal of adjacent trees whose roots were intertwined or which protected other trees from sunscald or other environmental factors

Construction damage to roots and soil may not be visible until a year after the project is completed, usually beginning as branch dieback in the canopy.

The root of the matter

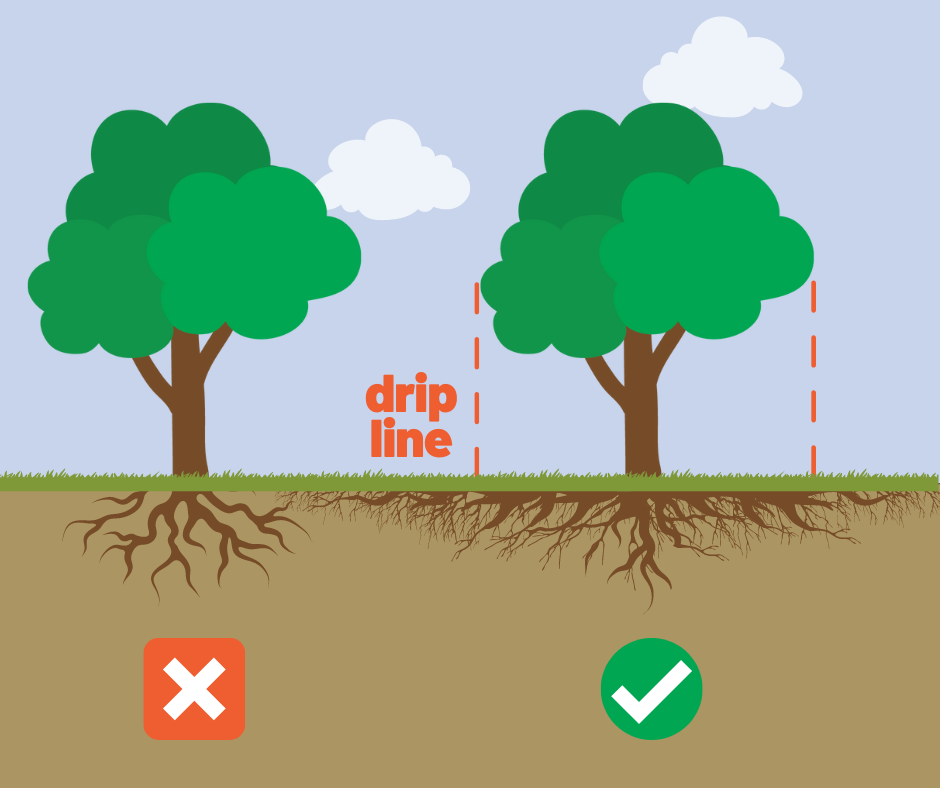

There’s a common misconception that tree roots are only tap roots or only extend to the dripline (the edge of the tree canopy). However, it’s important to realize that roots can extend 2-3 times beyond the dripline and most roots are in the top 18 inches of soil. Even relatively shallow excavation can cause damage. Additionally, root development varies based on many factors, most significantly species and environment, including soil type. Roots provide essential functions to trees including anchorage (stability), absorption and transport of water and minerals, and storage.

Root retention is of the utmost importance in the urban environment as they already struggle with uninhabitable soil layers, underground infrastructure, impermeable pavement and the like. Significant root cutting can be dangerous.

How to Preserve Trees During Construction:

There are many guides for best practices in preserving trees during development. The simplicity or complexity of your preservation plan depends on the scale of your project.

Note: Consider preserving soil in future planting areas in addition to preserving existing plants. Once compacted, soil can take decades to regenerate.

- Take an inventory and decide which trees to preserve. This should be done during the planning phase so trees are considered when designing. What trees (or other valuable natural resources) do you have? What species? How old are they? Are they in good health? Are they habitat for birds or raccoons? Decide which trees will be protected, transplanted or removed. You will likely need the help of an arborist. Make changes to the construction plan based on protecting certain trees. Specific strategies can be employed like pruning roots where root loss will occur and immediately backfilling, having a watering system set up, using tunneling instead of trenching, etc.

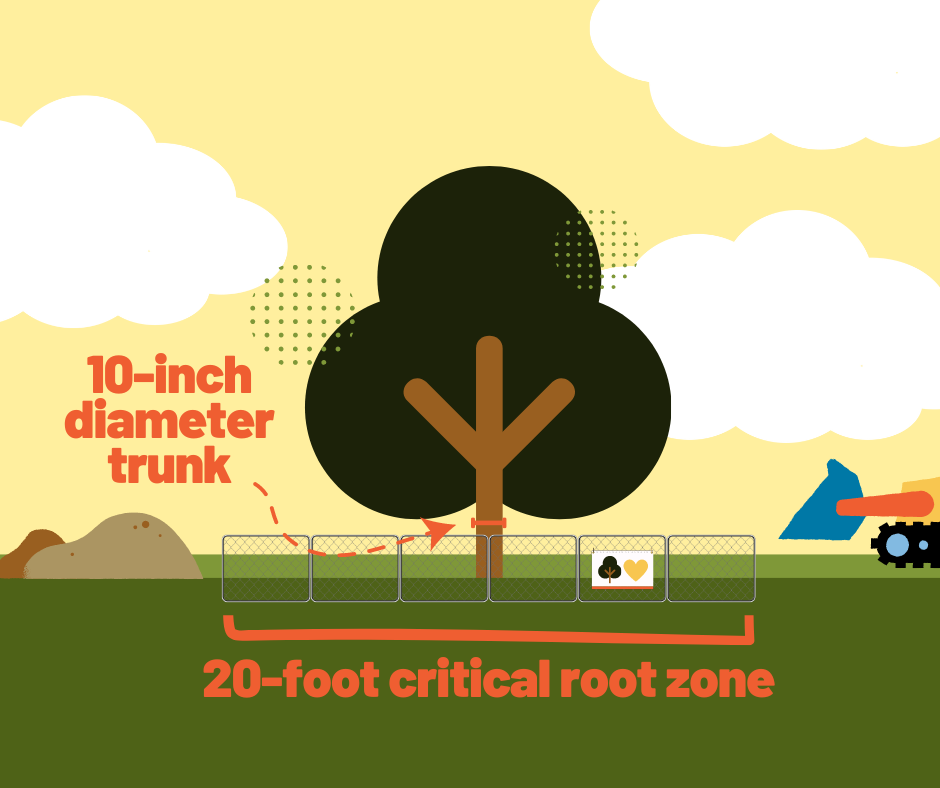

- Estimate tree protection zones for trees that will be kept. It isn’t enough to just avoid hitting trunks with machines. Trees have critical root zones (CRZ) where roots must be protected. Tree protection zones are the areas surrounding trees, including the CRZ, where roots and soil must be protected. There are multiple methods to estimate protection zones. One method is to simply define your protection zone as the tree’s dripline. A better indicator is trunk diameter. Measure the diameter of the trunk at breast height (4.5′ above ground) in inches, multiply that number by two, and then convert to feet. City code in Austin, Texas assigns acceptable levels of disturbance for each section of the CRZ, which may be more realistic. One more precise method is to consider the damage tolerance and age of the tree in the multiplication factor. Matheny and Clark’s Trees and Development: A Technical Guide to Preservation of Trees During Land Development offers those guidelines for more complex projects. See table at bottom of page for damage tolerance of species common in Kansas City.

- Set up the tree protection zones. Fencing should be set up around the perimeter. Orange safety fencing is commonly used, but can be easily moved or crossed. Freestanding chain link fence works well, but it can cause damage if it falls against the trunk. Hang signs that clearly label the space inside the fencing as the tree preservation area and do not enter. Consider all languages spoken onsite. Sometimes entering tree protection zones is unavoidable. In this case, you can help prevent damage with 6-12 inches of mulch or plywood over 4-6 inches of mulch. Identify areas the construction team can use that are outside of the protection zones for entering the worksite, parking equipment, storing soil and supplies, refueling equipment.

- Educate the construction workers. Have a meeting or walkthrough about the tree conservation plan before work begins. You could make a lasting impact by informing contractors or workers about preservation of roots and soil; knowledge they can take with them to future construction projects.

- Monitor the project until the very end. Be a lingerer for the sake of your trees. Ensure tree protection zones are truly being avoided. If branches are broken, they should be properly pruned back to prevent further damage. If the bark is wounded, it should be treated immediately if it is an oak.

We’re hopeful that someday everyone will choose trees and environment over development or convenience. In the meantime, KC Parks is working tirelessly to update the City tree preservation ordinances to help prevent unnecessary damage. Smaller communities in our area like Prairie Village and Mission Hills already have ordinances which require planning and protection for trees. If you see someone damaging city street trees or other public trees in Kansas City, contact 311. If you’re with a municipality looking for guidance on tree protection, take a look at the model ordinances that MARC put together.

Need help teaching your neighborhood or group about tree preservation? Contact our Heartland Tree Alliance team at trees@bridgingthegap.org or (816) 561-1087.

Common Kansas City trees and their construction damage tolerance

Source: Matheny and Clark’s Trees and Development: A Technical Guide to Preservation of Trees During Land Development

| Common name | Scientific name | Tolerance |

| Norway maple | Acer platanoides | Moderate-Good |

| Red maple | Acer rubrum | Moderate-Good |

| Silver maple | Acer saccharinum | Poor-Moderate |

| Sugar maple | Acer saccharum | Poor-Moderate |

| Ohio buckeye | Aesculus glabra | Poor |

| Tree of heaven | Ailanthus altissima | Good |

| Serviceberry | Amelanchier spp. | Good |

| Pawpaw | Asimina triloba | Good |

| Birch | Betula spp. | Moderate |

| American hornbeam | Carpinus caroliniana | Moderate |

| Hickories and pecan | Carya spp. | Moderate-Good |

| Catalpa | Catalpa spp. | Moderate-Good |

| Hackberry | Celtis spp. | Moderate-Good |

| Redbud | Cercis canadensis | Moderate |

| Flowering dogwood | Cornus florida | Poor-Moderate |

| Ash | Fraxinus spp. | Moderate-Good |

| Ginkgo | Ginkgo biloba | Good |

| Kentucky coffeetree | Gymnocladus dioicus | Good |

| Walnut | Juglans spp. | Poor |

| Easten redcedar | Juniperus virginiana | Good |

| Sweetgum | Liquidambar styraciflua | Poor-Good |

| Tulip tree | Liriodendron tulipifera | Moderate |

| Southern magnolia | Magnolia grandifloria | Moderate |

| Crabapples | Malus spp. | Moderate-Good |

| Mulberry | Morus spp. | Moderate-Good |

| Black gum | Nyssa sylvatica | Moderate-Good |

| American hophornbeam | Ostrya virginiana | Moderate |

| Spruce | Picea spp. | Moderate-Good |

| Pine | Pinus spp. | Moderate-Good |

| London plane | Platanus x acerifolia | Poor-Good |

| Sycamore | Platanus occidentalis | Moderate-Good |

| Black cherry | Prunus serotina | Poor-Moderate |

| White oak | Quercus alba | Poor-Good |

| Swamp white oak | Quercus bicolor | Good |

| Shingle oak | Quercus inbricaria | Good |

| Bur oak | Quercus macrocarpa | Moderate-Good |

| Chinquapin oak | Quercus muehlenbergii | Good |

| Pin oak | Quercus palustris | Moderate-Good |

| Northern red oak | Quercus rubra | Moderate-Good |

| Shumard oak | Quercus shumardii | Good |

| Post oak | Quercus stellata | Poor-Good |

| Sassafras | Sassafras albidum | Good |

| Cypress | Taxodium spp. | Good |

| Linden | Tillia spp. | Poor-Moderate |

| Elm | Ulmus spp. | Moderate-Good |

Sources:

Fite, K., & Smiley, E. T. (2016). Managing Trees During Construction. International Society of Arboriculture.

Matheny, N., & Clark, J. R. (2000). Trees and Development: A Technical Guide to Preservation of Trees During Land Development. International Society of Arboriculture.

Arkansas Forestry Commission. (2000). Natural Resource Management in the Urban Forest.

The City of Austin. Tree and Natural Area Preservation. The Critical Root Zone | AustinTexas.gov.

Day, S. D., & Wiseman, P. E. At the Root of It. International Society of Arboriculture.